Since the advent of the Common Core, states have demanded that students grapple with and “learn from” complex texts. This has resulted in teachers using a primarily text-based mode of instruction: instruction is dominated by Close Reading of the text that focuses on a “comprehension skill” like finding the main idea and details. Then, students spend the majority of class time working on a task that requires analyzing that text in order to complete it, e.g., a graphic organizer, a worksheet with questions requiring responses, etc.

The problem is, many kids, especially Emergent Bilinguals can’t access the text because of a lack of 1. background knowledge around the topic, 2. decoding skills, 3. oral English needed to recognize the sounds that make up words and the meanings of those words.

The writers of the Common Core have made a fatal assumption: reading comprehension, i.e. critical thinking, can be taught as a set of isolated, abstract skills.

The thinking has been, the more kids are exposed to complex texts and taught these skills explicitly, the better readers they will become. In fact, as Natalie Wexler so brilliantly points out in her new book The Knowledge Gap, teaching reading this way has resulted in a generation of kids who don’t read well and don’t like to read. They’ve learned skills at the expense of knowledge. Teachers have also been the victims of implementing a method of reading instruction – promoted by the state, taught in teacher preparation programs, and embedded in high-stakes testing design – that is completely disconnected from the evidence provided by the research on reading.

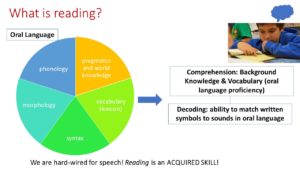

Reading consists of two major components, background knowledge (how much do you know about the topic at hand?) and decoding skills (how quickly and accurately can you get the words off the page?)

It is a well-established finding in cognitive psychology that deficiencies in either of these components – no matter if the student is proficient in English or still learning it – leads to a breakdown in reading comprehension.

I have spent time in my previous blogs explaining how oral language is the basis of literacy . When students don’t yet have sufficient oral language skills to apply to reading, which many of the five million ELs in the United States don’t, there must be a fundamental shift in instruction: from text-based to oral-based.

Recently I modeled for teachers of middle and high school Spanish-speaking ELs how they could teach in an oral-language mode the story of “I am Malala”, the Pakistani women’s rights activist who was shot by the Taliban and lived. In it I show how to develop students’ background knowledge and oral language of the topic by eliciting concrete information through explicit questioning around what students See Think and Wonder about the images, and then having them sort images into the key concepts in a text, like you can see teachers doing here in my workshop. Students discuss and develop critical thinking around pictures in English and their Home Language.

In this way, the teacher bypasses teaching through the text and develops students’ oral language first. That’s not to say students won’t be exposed to text, just that in order to have a chance of accessing text, they first need to build background knowledge and vocabulary orally.

We need to stop giving kids texts they can’t read and expecting them to complete tasks through them. Instead, we need to give them the fundamental tools they need to get reading: oral language development, background knowledge, and decoding practice.

Teachers, what do you think? Comment below!

Leave a Reply