Happy 4th! In July, all children are aebll wants to profile specific groups of diverse English Learners so that readers can gain a more in-depth understanding of their linguistic needs in school. This week I’m going to introduce you to Samira (*not an actual student), an adolescent newcomer with developing literacy.

It’s a common – and not unreasonable – assumption that an adolescent newcomer with no English can arrive in the United States, and with hard work, time, and determination, can (and should) learn English and succeed in school.

While there are certainly many high achievers – immigrants are some of the most resilient students you’ll ever meet – many have different academic pathways and often fail school due to complex and compounding factors like family separation, school characteristics, and the level of academic English proficiency they are able to achieve.

It’s difficult to put ourselves in others’ shoes. But adolescent newcomers – especially those with developing literacy -have unique needs that are imperative to understand if we want to set them on a trajectory of success in school and life.

Who are adolescent newcomers with developing literacy?

Samira is fifteen years old and arrived one year ago from Yemen with her family, refugees of the violent ongoing civil war, which has killed thousands and caused famine for 20 million people. Prior to arriving in the U.S., her family spent 3 years in the Markazi refugee camp in Djibouti. Because of the circumstances, Samira has not attended school regularly, or at all, since the age of ten.

Through the United Nations Refugee Program, she was able to come to the U.S. with her parents and siblings. Her family is adjusting to a new life in NYC, but Samira is traumatized from being exposed to violence, losing her home, and experiencing famine.

She enrolled in her local high school in the Bronx last fall and is still struggling with oral English but is making gains in proficiency. She loves school and is a motivated student. However, she has been unable to keep pace with the demanding curriculum that requires she read complex texts and write multi-paragraph essays. Although Samira has elementary literacy skills in Arabic, she has struggled to transfer those skills to the task of decoding in English and doesn’t have the vocabulary or academic content knowledge to make sense of text. Even with ENL services, she is behind her other English Learner peers.

She is responsible for taking care of her three younger siblings and cooking while her parents work. Since the school closures in March, Samira has been quarantining inside her family’s apartment, with little peace and quiet to study. Her teachers report that they have not been able to contact her since May.

what we know

According to the NYC Department of Education (DOE) English Language Learner Demographic Report, 32,275 newcomer students (out of the city’s 154,276 English Learners) entered middle and high school during the 2018-2019 school year. Of those, almost 5,000 were classified as Students With Interrupted or Inconsistent Formal Education (SIFE). The three top countries of origin of SIFE are the Dominican Republic, China and Yemen.

A SIFE is defined as a newcomer (has attended school in the U.S. for less than 12 months) who is determined upon enrollment to be 2 or more years behind grade level in home language literacy and math. In reality, many are at about a third grade level, and a small minority is completely new to print (Klein & Martohardjono, 2006, 2009). Another reality check: many students go unclassified, as screening methods are inconsistent and the state does not report numbers outside of NYC.

While not all adolescent newcomer students with developing literacy fit Samira’s profile, generally speaking they are a group that has experienced traumatic and harsh life circumstances that can psychologically impair their ability to adjust to a U.S. classroom (and now remote learning) environment.

socio-emotional well-being is everything

There is no denying that this very special group of students have unique socio-emotional needs that need to be addressed at school. Among those are ensuring that students feel comfortable and safe (and not risk reliving traumas), making a point to include their cultures and life experiences in the learning process, and not assuming they know what is expected of them in a school setting (e.g., modes of appropriate student-teacher interaction; completing assignments; independent studying). In these times of school closures, a teacher or community liaison calling home on a regular basis might be the difference between a student returning to school or not. Without these needs being met first, we cannot begin to meet their linguistic needs.

students need their HOME language to learn

Adolescent newcomers are older children who have acquired fluent and complex oral proficiency in their home language (HL): they come to the classroom with conceptual and world knowledge, vocabulary, phonology and morpho-syntax (see my mini-lecture on What is Oral Language? ). They are NOT cognitively or linguistically impaired.

On their journey to acquire English, one of the most powerful strategies a teacher can use is to have them discuss content in the HL. If we insist on an English-only classroom or don’t support multi-lingual modes of learning, we are effectively cutting them off from the critical thinking they need to do to grasp content. This doesn’t mean that they should only use their HL, just that we understand that their HL is a launching pad for English acquisition.

Students can:

- work in same-language groups or with partners, then look up words or use Google Translate to respond in English to specific prompts.

- Remotely, they can respond in their HL on Flipgrid (even if the teacher doesn’t understand, a partner student can paraphrase and respond to the post).

- be in live small-group instruction, then confer and summarize information in the HL;

- or work in teams and talk to each other over the phone before they respond to a prompt.

let learning be oral

Speakers don’t learn to read in a vacuum (see my mini-lecture on What is Reading?). Just as young children apply their knowledge of sounds to the task of learning symbols on the page, adolescents still developing literacy need a chance to acquire basic English oral competency before they can apply sounds to symbols. If they don’t know how to pronounce words or phrases in English, how can they be expected to recognize sounds in words in text?

This is going to take a while; in fact while basic oral communicative competency can take approximately 1-2 years, academic language (see my mini-lecture What is Academic Language?) takes anywhere from 5 to 7 years or longer to develop (Cummins, 2001).

What do we do in the meantime? A teacher of SIFE needs to make a shift in instruction, from text-based to oral-based. Students are not going to learn from text as the Common Core is requiring they do. What exactly does this mean? There are three broad principles a teacher can follow:

- Teach the content through pictures and video, and have students respond to those pictures (Watch a See Think Wonder activity).

- Read complex text aloud to your students, break it down for them and have them summarize it orally (See Syntax Knowledge to Practice by Gillis & Eberhardt).

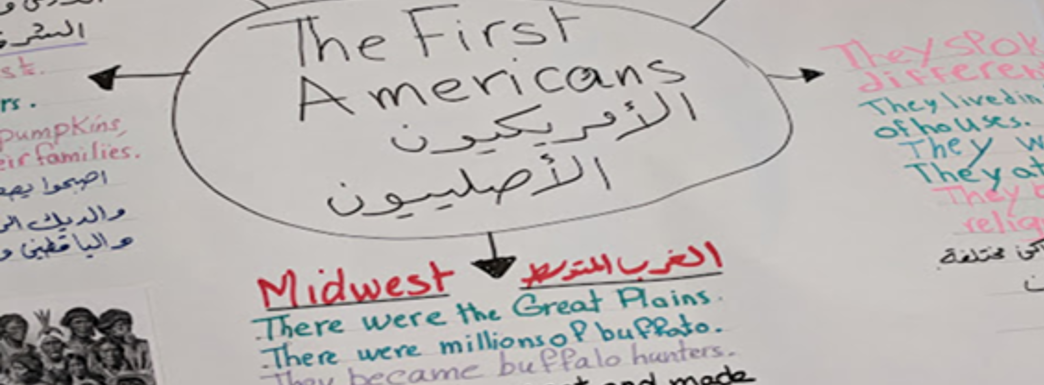

- Create written text collaboratively as a group (Language Experience Approach). Here’s a sample of a Concept Map that students created:

To see how this all fits together into a model lesson, see my NY State tesol webinar and materials.

teach tudents phonics and word parts when they are ready

While a newcomer with little English or HL literacy is not going to be ready to start decoding in English, a student who has a bit more oral language can begin studying sound-symbol correspondence and recognizing prefixes, roots and suffixes. Word work is especially beneficial for Spanish or French speakers, since they share Latin sources of vocabulary with English (see this video of word work instruction in different grades).

Teachers can download a ruled, tracing font like KG Dots Primary (free on TPT.com) and create worksheets that support handwriting practice and phonics/word work – like this Sample Worksheet for SWDL. For secondary teachers who are not familiar with how to teach decoding, see this free, self-paced course on Reading Rockets.org. And stay tuned because I want to provide a special course for secondary teachers this year!

stay tuned for more profiles of diverse learners

Teachers, let me know what you think! How can I help you with your students? Comment below or DM me @AEBLL_Children.

I wish all of you a wonderul and safe July 4th weekend! Stay tuned for next week’s blog on our littlest learners!

Leave a Reply